Core training after pregnancy demands patience and a back-to-the-fundamentals approach. This is because growing a baby changes your structure in major, long-lasting ways. Given these shifts to your alignment and anatomy, one of the best things you can do to support your return to athletic activity postpartum is to strengthen your core globally. Core training after pregnancy, and in general, isn’t about doing a million crunches to cultivate a six-pack. The goal is a functional core: a core that supports you as you eventually layer on more strenuous strength work and learn to move again with good postural and pelvic control.

This article is the first in a series discussing how to resume training in a safe way postpartum, with a solid foundation of support through your pelvis and core. While this is specifically geared toward women who have recently had a baby, the concepts and application are relevant for anyone, man or woman. Perhaps you’re new to a sport or strength training, or maybe you’re struggling to get over recurring, chronic, or migrating injuries. It could be that you’re looking to return to training after a hiatus of several months. No matter your background and motivations, it is important to know how the core functions—and not to overlook it. A healthy core is vital to athletic performance.

Overview of the Core

To understand the core, you must first understand the anatomy of the abdomen and pelvis and how these relate not only to movement but also to standing and good posture.

The Rectus Abdominis and Obliques

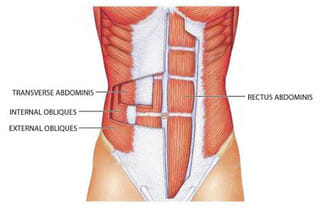

Working from the most superficial muscle to the deepest abdominal muscles, we’ll start with the rectus abdominis (RA), better known as the six-pack. This muscle attaches at the sternum and the pubis. Because of its length, it is divided into segments by connective tissue, giving it that washboard look.

There are many exercises that we’re all familiar with—sit-ups, crunches, and the like—that strengthen the RA. While a strong RA looks good, it does little to support your spine or pelvis. It can even lead to injury if the deeper muscles, primarily the transversus abdominis (TA), aren’t engaging.

Deeper than the RA are two layers of obliques that attach to the lower ribs and the top of the pelvis (the ilia bone, to be exact). As the name implies, one layer goes one way, the other layer the other way. This oblique muscle fiber direction means that when one side contracts, your ribcage draws toward the opposite hip. When both sides contract, they provide support for torsional forces.

The Transversus Abdominis

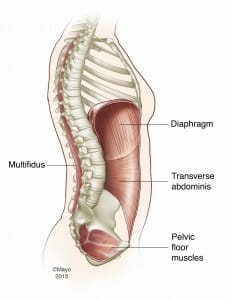

The deepest abdominal muscle is the transversus abdominus (TA). Attaching along the ribcage, the lumbar fascia (connective tissue in the back), and the rim of most of the ilia (front hip bone), it creates a supportive jacket around the spine. While the obliques and RA play a role in stabilizing the core, the TA is more relevant postpartum.

The Diaphragm

Just as important as the TA is the diaphragm, which separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. It has tendinous junctions all along the lower six ribs and the posterior (back) of the xiphoid (the bottom part of the sternum), as well as part of the lumbar spine’s connective tissue. While that might not seem too relevant for the core, the TA, quadratus lumborum, and psoas muscles (additional muscles connecting the upper and lower body) all fascially connect to the diaphragm, making it crucial in lumbar stability.

Functionally, the diaphragm is our primary muscle for respiration. When we inhale, it contracts and flattens, creating space for the lungs to expand, and air draws in. During exhalation, the diaphragm relaxes and returns to its dome shape along the bottom of the ribcage, expelling air from the lungs. Ideally, the diaphragm also syncs with the pelvic floor muscles to provide much-needed stability to the pelvis, especially during movement.

Pregnancy and the Core

Pregnancy and the culmination of labor and birth is a doozy for the body. As the baby develops, there is less space for the diaphragm muscle to expand, the ribcage often tilts to create space in the abdomen, and the back muscles respond by shortening. Your pelvic ligaments soften to ready for childbirth, and your abdominal muscles stretch and shift to accommodate the growing baby; taken together, those changes lessen your overall thoracic and pelvic stability. Then the delivery itself—either vaginally or by Caesarian—wreaks havoc on your pelvic floor and core muscles. It’s no wonder that it can take months or even years to feel back to “normal” after giving birth.

Once you feel you are ready to bring your core back online, start gradually. A subsequent article will outline a beginning workout that will help you develop good postural habits and deeper core control.

DISCLAIMER

This article is for general information and not medical advice. It’s important to discuss your return to activity with your doctor. Every woman and pregnancy is unique and should be respected as such. If you have a more serious condition like diastasis recti, I highly recommend working with a PT who specializes in women’s health and postpartum wellness.