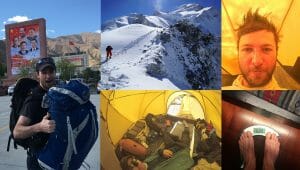

This is how David Roeske became the fourth person ever to successfully climb Everest and another 8,000-meter peak, in his case Cho Oyu, without oxygen in the same season.

Part One: Braving Hypoxia on Cho Oyu

During the long flight from New York to Doha, Qatar, I had time to reflect on the seriousness and uncertainty of the journey I was about to undertake. We were cruising along comfortably above 30,000 feet, just a bit higher than the summit of Everest. I shivered a little, not knowing what the next weeks might bring, what condition my body would be in on the return flight, or if I would be around for the return flight at all. Still, I could hardly contain my excitement.

In Kathmandu, the expedition leaders did gear checks and picked up our Chinese visas. I was already feeling antsy about all the time that had gone by since my last big workout. After a couple days, we boarded what should have been a short flight to Lhasa, the 12,000-foot capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region. After getting diverted to Chengdu for a day due to high winds in Lhasa, we finally arrived in the Himalaya. It had been close to a week since my last workout. I could feel the clock ticking.

After a couple days acclimatizing in Tingri, an old trading post town at 14,000 feet, we started driving to the Cho Oyu Base Camp, at 16,000 feet. We spent another couple days adjusting there before hiking to Interim Camp, and then a day later to Advanced Base Camp (ABC) at 18,700 feet. The anticipation builds and builds as you get closer to the mountain, but you have to hold yourself back and let your body adapt at a measured pace.

I got to Cho Oyu’s ABC on May 2. My initial plan had been to summit around May 10 to give myself a few days to rest and drive over to Everest. After talking to some of the other teams on Cho Oyu, though, we learned that a big storm was forecast to start around the ninth, and leave the mountain socked in for over a week. I knew that if I waited for that storm to clear before attempting Cho Oyu, I wouldn’t have enough time to try Everest as well. I was faced with a difficult decision. I could either try to summit early before I was acclimatized—risking failure to summit, or worse—or I could wait, and give up on my primary goal of returning to climb Everest without oxygen.

My partner on the mountain, Lhakpa Gelbu Sherpa, was friends with another famous Sherpa, Chhiring Dorje, who had already done an acclimatization rotation on the mountain with his clients, and was going to attempt the summit on May 7. Lhakpa and I weighed the options, and decided we should join them. There would be no acclimatization climb for this attempt. After one rest day in ABC, we began our ascent.

We made rapid time on our way to Camp 1 at 21,000 feet, which was an encouraging sign of fitness. I had a little headache, but was still feeling good. We took one rest day to melt and drink as much water as possible, then continued to Camp 2 at 23,300 feet. We arrived in the evening, set up camp, and got ready to head for the summit at 3:30 a.m.

We were nearly at Camp 3 when the sun began to rise. I turned to look over my shoulder to take it in, and was floored by the alpenglow spreading across the peaks and glaciated valleys in all directions. I was so concerned with trying to keep a steady pace that I almost didn’t stop to take a picture.

As we paused to fix a rope through the rock bands that guard Cho Oyu’s summit ridge, I took stock of my body. I had to be very conscious of how I was responding to the altitude. My toes were cold, so I connected some battery-powered toe warmers, and I had an occasional cough, but there still were no signs of altitude sickness. I felt hypoxic, but clearheaded.

We got through the technical rock band above Camp 3, and reached the summit ridge, which is gentle but agonizingly long. It can take a couple of hours to traverse even though you are already almost at the summit elevation. The clear skies at dawn had become overcast, so we couldn’t see the views of Everest that Cho Oyu is famous for, and we also couldn’t see how much farther we had to go to reach the top, so we kept trudging on. I sent my girlfriend a text from my InReach tracking device: Close to summit but very tired.

After a long time on the ridge, I was feeling even more hypoxic, almost dreamy. I was on the verge of turning back, but each time I checked myself for symptoms of altitude sickness I seemed generally OK. I had no headache, no difficulty walking straight, and no severe coughing. I was also keeping up with the rest of the team, so I kept putting one foot in front of the other.

I was very close to calling it quits when we found the summit marker. There were no views, just a snowy plateau in all directions. I was so grateful—not only to make the summit, but also to reach the turnaround point! We snapped some pictures and quickly roped up for the descent.

On the way down, all of us were exhausted. We stopped and sat down over and over again to rest for a few minutes at a time. Each time, I would have a little mini-nap, once or twice starting to dream, and then force myself to get back up and walk another few hundred feet. After one of these rest breaks right above the rock band, I mentally yelled at myself to wake up and focus before I fed my figure 8 device for the rappel. I could tell how easy it would be to make a mistake clipping in, and take a few-thousand-foot tumble down the mountain.

We summited around 3:30 p.m., 12 hours after starting, and it took us another 4 hours to get back down to Camp 2. I sent a message to my girlfriend: Just got back from my hardest day ever… Dug so deep. I hope it wasn’t at too high a cost. Was very hypoxic at the top. Felt a little crazy and in a dream. My Sherpa and I were so exhausted that we didn’t even melt water when we got to camp; we collapsed in the tent, and went straight to sleep. It’s crazy what a day of exposure to such extreme altitude can do to you.

Back at Base Camp, I met up with my original team, who were still waiting for the coming storm to pass. Slouched over the table in the dining tent, I commented, “Why on earth do we do this?” When I expressed my weakened appetite for Everest, they all laughed at me.

“Give it a few days,” they said. “It’ll be back.”

They were right.

Part Two: 40 Hours in the Death Zone—an Epic on Everest

On May 12, only five days after I stood on the summit of Cho Oyu, I made it to Everest’s Tibetan Base Camp, just as most of the climbing teams were coming down to rest in lower villages after their second rotation on the mountain. Lhakpa and I stayed in the mostly empty Base Camp for a few days until it looked like weather might be improving higher up. Then we began our trek to ABC.

We covered the 6 miles to interim camp in just under 3 hours, rested the night, and arrived at ABC (21,000 feet) on May 16. At this point, I was still hopeful I’d be able to summit Everest without oxygen, but the enormity of the task made me uncertain about my chances.

After a couple days at ABC, forecasts indicated a weather window was approaching. Again, I was torn about how to proceed. I wasn’t sure if I needed more acclimatization after Cho Oyu. Part of me wanted to go to Camp 1 and sleep a few nights there, and maybe even come back to ABC before a summit bid. But on the other hand, I knew that might weaken me too much for the summit. Once again, Lhakpa and I decided to go for a single push, with one rest day at Camp 1. I hoped it would be enough.

We headed to Camp 1 in the afternoon of May 19, four days before the anticipated weather window. That far ahead in a forecast is always a gamble, but I thought it would be my best opportunity. I was really happy with my fitness level during that climb. I remember in 2013 taking 4 or 5 hours on some of my trips to Camp 1 from ABC. This time, it took us 3 hours and 10 minutes to reach the 23,000-foot camp at the North Col. I am sure that improvement came from the training I did with Scott and Steve (read about how David trained for Everest). I also felt really fortunate that I had managed to maintain some fitness after Cho Oyu.

We took one rest day at Camp 1, and then on May 21 headed up to Camp 2. By the time we got to the beginning of Camp 2 at around 24,900 feet, we found almost all of the tent sites were taken. So Lhakpa and I kept climbing higher and higher. Camp 2 stretches along a ridge for hundreds of feet of elevation, and we ended up finding a spot near the very end, at around 25,500 feet. I was worried about how much it was going to take out of me to sleep that high, but that was the only option. We pitched our tent, settled in, and tried to get some rest.

We got a late start the next day. A lot of people had already started the climb to Camp 3. We finally got going at what felt like a slow pace. I didn’t feel particularly strong, but I noticed I wasn’t falling behind the other climbers on oxygen who were spread out ahead of me.

As I neared Camp 3, my pace slowed further. I would hike one or two steps, stop and breathe 10–20 times, and then repeat. Finally, we made it to Camp 3 at 26,900 feet—the same height as Cho Oyu’s summit! We put up the tent, crawled in, and tried to rest for a few hours as it snowed outside. I was stressed about the added difficulty of climbing in fresh powder.

After a few hours of napping, we began suiting up and melting water. Sometime after midnight we got on our way. The route was much busier than it had been in 2013. I remember feeling stronger than the pace the queue was moving, and I was considering stepping off the fixed lines to pass some people. But then I thought that maybe the slow pace was exactly what I needed to succeed. It occurred to me that their holding me back a little bit might keep my body from revving its engine a little too high, and triggering HAPE or HACE. So I accepted the pace, and was glad that I could keep up at all.

When I started that morning, I thought I might have about a 40 percent chance of summiting. I knew how difficult it was to climb Everest without oxygen, and I was on a hair trigger to turn back if I started to develop signs of altitude sickness. The main reason I was climbing with a Sherpa who was on oxygen, in fact, was that I wanted to be with someone I could trust to keep tabs on my condition.

Somewhere on the summit ridge, though, Lhakpa and I got separated. I saw him step off the line to relieve himself, and thought he would rejoin me momentarily, so I continued to move up slowly with the queue. I soon found myself at the bottom of the Second Step, the largest cliff you have to climb on the North Side of Everest. My feet were cold, but not so cold I thought I was getting frostbit. I stood somewhat nervously waiting my turn to clamber up the dangling ladders strung over the cliff, looking around for Lhakpa. He was nowhere in sight.

At this point, though, I was on autopilot. Hypoxia has a way of giving you mental tunnel vision. You walk a few steps, catch your breath. Walk again. I kept wondering when I’d start to cough or get a headache or feel confused. But I was able to keep moving and none of those symptoms came. The Third Step passed, then the summit pyramid, which you have to traverse around, climbing some last rocks before cresting the final summit ridge. Only when I made that final ridge did I let myself believe I would actually succeed. Suddenly, I was at the top again.

“In my state of spiritual abstraction, I no longer belong to myself and to my eyesight. I am nothing more than a single narrow gasping lung, floating over the mists and summits.” —Reinhold Messner

“In my state of spiritual abstraction, I no longer belong to myself and to my eyesight. I am nothing more than a single narrow gasping lung, floating over the mists and summits.” —Reinhold Messner

I was happy to be there, but with no supplemental oxygen I wanted to get down as soon as possible. I thought Lhakpa was right behind me, and expected him to join me in a few minutes, but he didn’t appear. I felt compelled to wait for him, but I was beginning to feel desperate to get down. I knew I was frying brain cells with every passing minute. It ended up taking him another 45 minutes to arrive. We quickly took some photos, and then began heading down.

The climb of Everest had actually gone better than the Cho Oyu climb, even though it was longer, and I had felt less hypoxic at the top. But the descent was just as exhausting, and I stopped to rest many times along the way down.

Finally, we made it back to Camp 3. I wanted to continue descending but Lhakpa had developed snow blindness and was having trouble seeing. He didn’t feel comfortable continuing, so we settled into our tent for the night and used the one sleeping bag we had brought as a blanket. For me, this meant another night of sleeping above 26,000 feet, in the death zone, without supplemental oxygen. All in all, I spent over 40 hours in that zone.

The next morning when we began to head down, I was feeling completely ragged. The past night had taken a toll, and descending from Camp 3 to Camp 1 was slow and arduous, even though it’s downhill. Even at Camp 1, I wasn’t ready to celebrate. I still had the big headwall to get down, so I had to keep paying attention as I rapped the fixed lines.

Finally, we got down the headwall and I began to feel out of the danger zone at last. One of the camp cooks met me with hot orange Tang at the crampon point. I was so tired by then, that even though I was simply hiking down a normal mountain trail, only 30 minutes from ABC, I still had to stop every 50 feet or so to rest. I’ve never been that depleted in my life.

I slept the entire next day, except to get up for meals. My body was aching in a way I had never felt before. Normally, being sore after a hard workout feels good; but this pain felt wrong, unhealthy, alien. I had drained my internal batteries so low that even the recovery process hurt. Lying on multiple sleeping pads in the most comfortable position I could find, my body still ached.

As I walked into Base Camp a couple days later, I found myself thinking back to something I heard Reinhold Messner say: “The reason we climb is not for the summit—the summit is just the turnaround point—the reason we climb is for the rebirth experience you have when you return to camp.” For me, that rebirth was powerful indeed.

When I got back to civilization, I checked with the Himalayan Database and found that only three other people had ever summited Everest and another 8,000-meter peak on the same trip without supplemental oxygen before. Of those three, one sadly passed away on the descent. I was incredibly lucky, and I’m incredibly grateful.

When I got back to the US, it was amazing how weak I was. Within a couple weeks of eating, my weight bounced back. But it took a few months to get back in shape, as my muscles were much slower to recover. Just like they have in the past, though, the memories of the suffering have begun to fade, and the call of the high mountains and the rebirth I find in them remains strong. Already, I feel the need to return.

-by David Roeske